Roberto Giacomelli

•1975, Nebraska. Burt e sua moglie Vicky sono in viaggio in auto e nel bel mezzo di un’accesa discussione tra i due, un bambino spunta improvvisamente dal campo di grano turco che costeggia la strada, con l’inevitabile conseguenza di essere travolto dall’auto. I coniugi sono nel panico perché pensano di aver ucciso il bambino, ma guardando bene, Burt si accorge che il bambino ha la gola tagliata e dunque non può essere stato l’impatto con la sua vettura la causa della morte. L’uomo nota inoltre di essere osservato da qualcuno che si nasconde nel grano turco, carica il cadavere in macchina e si dirige al paese più vicino per denunciare l’accaduto. I due giungono così a Gatlin, che a primo impatto sembra una città fantasma, ma in realtà è abitata da una comunità di bambini dediti al culto di “Colui che cammina tra i filari”, una divinità pagana legata al grano turco che esige gli adulti in sacrificio per rendere prospero il raccolto.

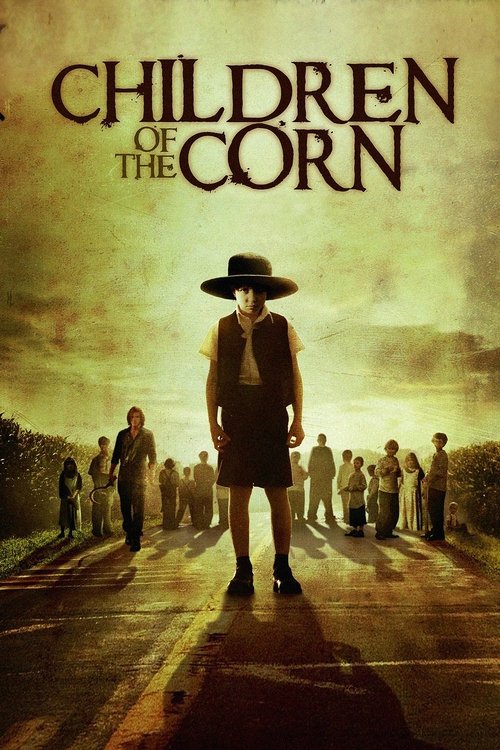

Quella di “Children of the Corn” è stata una sorte anomala. Un racconto di Stephen King pubblicato nella raccolta “A volte ritornano” intitolato appunto “Children of the Corn” (“I figli del grano” in Italia) viene adattato per il grande schermo nel 1984 da Fritz Kiersh e diventa – per il mercato italiano – “Grano rosso sangue”. Da quel momento è scattata un’operazione cinematografica che ha

dell’assurdo: poche pagine scritte da King sono diventate spunto per una sequela di film che ad oggi contano 8 titoli, compreso un remake, questo “Campi insanguinati”, prodotto direttamente per la tv via cavo americana.

Il materiale narrativo di partenza è molto buono e questo è merito di King e della sapiente rielaborazione del fanatismo religioso applicato insolitamente alla dimensione infantile, come a creare una variante del fondamentale “Ma come si può uccidere un bambino?” di Serrador in chiave religiosa. Però bastava un film per dire tutto (e piuttosto bene, tra l’altro) quello che King aveva accennato nel suo racconto e creare una saga infinita appare operazione opinabile oltre che altamente superflua. Il risultato è che ogni film si limita a ripetere la storia del prototipo con piccole variazione di capitolo in capitolo con

l’impressione che ogni film sia una sorta di remake del capostipite dell’84. In un quadro simile arriva il vero remake che se da una parte possiamo considerare più onesto nell’esplicitare sin dal titolo l’intento, dall’altra è solamente l’ulteriore inutile film di una saga smunta e concettualmente estinta quasi 30 anni fa.

L’ambientazione temporale è quella “corretta”, ovvero il periodo in cui il racconto fu scritto e la vicenda ripercorre in modo inizialmente fedele quella raccontata nel film di Kiersh per discostarsene notevolmente nella seconda parte. Quello che colpisce è il drastico mutamento nella scrittura dei due personaggi principali, non più una classica coppia che trova nel proprio amore la forza di combattere la setta e il demone per cui predicano, ma una coppia sull’orlo del divorzio che ci viene presentata proprio nel mezzo di un acceso litigio. Lui è un veterano del Vietnam, interpretato da David Anders (“The Vampire Diares”; “Heroes”), forte e preparato ad ogni evenienza nonché tormentato dai demoni della guerra, lei una bellissima e aggressiva donna di colore (interpretata da Kandyse McClure di “Battlestar Galactica”) che sembra avere il reale controllo sull’andamento della coppia. Questa presa di posizione nello stravolgimento dello script originario fa onore allo sceneggiatore e regista Donald P. Borchers così come ne rappresenta il suo limite primario. Palesando fin da principio

la preparazione bellica di Burt possiamo immaginare in che modo reagirà alla presenza dei bambini assassini, annullando da subito il pathos verso la sorte dei protagonisti. Gli stessi, inoltre, sono stati troppo caricati di tratti negativi risultando per lo più odiosi, con la conseguente contribuzione all’annullamento della partecipazione emozionale dello spettatore. Il problema è che neanche tra le fila dei ragazzini esiste un personaggio forte che possa catturare l’attenzione e soprattutto viene a mancare l’elemento “buono” che nel film di Kiersh era rappresentato da due bambini che aiutavano la coppia a districarsi tra i mille pericoli di Gatlin. Qui ogni bambino è perfido e riprovevole e nessuno emerge sull’altro, a cominciare dall’anonimo leader Isaac (Preston Bailey) e dal poco incisivo Malachia (Daniel Newman), suo braccio destro.

A Borchers, regista di questo film, sembra interessare più che dei protagonisti positivi e dei personaggi in generale, di descrivere con acume quasi antropologico il vivere dei bambini dediti al dio del grano, con tanto di approfondimento sul loro ordine di successione e rituali di accoppiamento e morte.

Colpiscono qua e là alcune insolite scelte narrative capaci anche di spiazzare lo spettatore, non manca la concessione ai particolari più sanguinolenti ma nel complesso si ha la sensazione di aver assistito a un’inutile e assolutamente non giustificabile operazione mirata a sfruttare un franchise decisamente logoro.

Commenti