GG

Giuliano Giacomelli

•In a house in a Japanese residential neighborhood, a terrible curse looms that strikes anyone who enters or comes into contact with that dwelling. The first to notice this threat is Rika, a young volunteer who works as a social assistant and is sent to that home to take care of the elderly owner. But Rika will only be the first of a long list of people who will be struck by the curse and who will meet the strange presences that populate the house.

What is Ju-on? With this Japanese term, it refers to: "The curse of a person who dies in the grip of a furious anger that accumulates and then unleashes itself in the places where that person lived. Those who encounter it die, and a new curse comes to life."

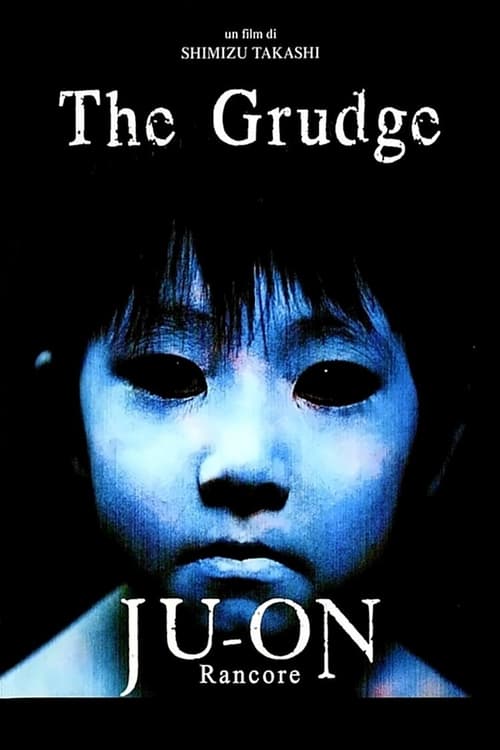

"Ju-on" ("Rancor" in Italian and "The Grudge" in English) is one of the first modern Eastern ghost movies to arrive in our country and, without a doubt, represents one of the most famous and acclaimed films in its genre, becoming a small Eastern cult in a short time.

The film was born as a television work in 2000 with the TV series "Ju-on", a series that achieved unexpected and stunning success, encouraging the producer, Taka Ichise, and the director-screenwriter, Shimizu Takashi, to work on a sequel for TV; and thus, in the same year, "Ju-on 2" was born. This second television chapter also received great success and moved and frightened millions of Japanese spectators, and thus it was decided that the next step would be directed towards the big screen: thus, in 2003, "Ju-on" was born, this time in a cinematic version written and directed by Shimizu Takashi.

But does "Ju-on" really have all the cards in place to be praised without ever frowning? To this question, everyone is free to attribute the answer that comes to mind, but it is fair to consider the work as a whole, highlighting its merits and pointing out its flaws.

The first and perhaps biggest mistake that the film offers us is its desire to be too faithful to the television series, to the point of not being able to develop an organic and somewhat engaging work because there is no real plot throughout the duration of the film, but the result is a combination of many small stories that open and conclude in a short time. And thus, we will not have a real protagonist in flesh and blood (although the figure of Rika prevails) but the supporting element (and therefore the protagonist) will become the cursed house.

A second aspect, which may make the "occidental" common eye frown, is the location that does not suit the tastes of Westerners, accustomed in our collective imagination to represent haunted houses with spectral, gloomy, lugubrious buildings that give chills just to look at them; in this "Ju-on" none of this is present (but it is surely dictated by the traditions and the decisively different culture). The haunted and cursed house is as normal as one can imagine, a simple modern building that stands on two floors and could therefore be everyone's house. And perhaps it is right here that one can grasp an intriguing and chilling aspect in making the "abode of evil" so normal and simple, that is, pushing the average viewer to think that something sinister and evil could lurk in their own home. Probably this is an aspect to consider, but the fact is that the average viewer does not stop to create such problems but limits themselves to judging what they see, and what they see in the location is certainly not scary.

But to these different narrative and scenographic problems, there are sequences that give you chills and ghost appearances that will be hard to forget. The realization of the ghosts, which ranges from little Toshio and his kitten to the mother Kayako, is really excellent and therefore many sequences in which they appear will be unforgettable; one above all is the fantastic and very famous scene at the end where Kayako is already groaning from the stairs emitting a chilling guttural sound that is hard to forget.

All this is offered to us by the opposition of Shimizu Takashi to adhere to the New Horror Movement, that is, a Japanese cinematic trend that flourished in the second half of the 1990s and that tells us that in a good horror nothing should ever be really shown, because if in a movie where there are monsters and supernatural elements you want to show too much you end up falling involuntarily into the ridiculous and therefore to create suspense and terror you need to darken and hide the figure of the ghost. But Shimizu, contrary to this trend, does not worry about falling into the ridiculous and decides to show the ghosts as much as possible, even when in reality there is no need at all. But in doing so, to scenes decidedly successful and terrifying in which horror must be shown, there are ridiculous, unintentionally comic and decidedly intrusive sequences (see the scene of the old man in the wheelchair who makes faces at the child ghost) that affirm what the New Horror Movement dictates to us.

Therefore, this "Ju-on" appears to us as a product only partially successful because, although it enjoys truly disturbing and scary scenes, it is let down by some naivety that could have been resolved in a much better way; moreover, as often happens, some characteristics, even if in tune with Eastern thought, do not find much acceptance in the characteristic thought of Western culture.