Andrea Costantini

•Siamo a Pontypool, una nevosa cittadina canadese. Grant Mazzy è il provocatorio speaker di una radio locale, il cui programma è carico di sarcasmo e volgarità. Durante la sua trasmissione, Grant racconta un fatto curioso che lo ha coinvolto mentre si recava al lavoro: una donna in evidente stato alterato che farfugliava cose senza senso. Durante la trasmissione arriveranno altre testimonianze di persone in stato confusionale e sia Grant che i tecnici della radio capiscono che sta succedendo qualcosa di grosso e spaventoso là fuori. Addirittura alcuni testimoni raccontano di aver visto persone che si mangiavano a vicenda.

Spesso, negli ultimi anni, le tre cosiddette unità aristoteliche di tempo, spazio e azione sono state prese, maneggiate e sconvolte nel cinema, soprattutto nel genere che tanto amiamo. Film come i vari “Paranormal Activity”, interamente ambientati in una casa oppure, ancora più estremi come “Buried”, la cui storia è narrata per tutta la durata del film dall’interno di una bara, hanno fatto qualcosa di più che lanciare una moda: hanno stabilito le nuove regole della tensione.

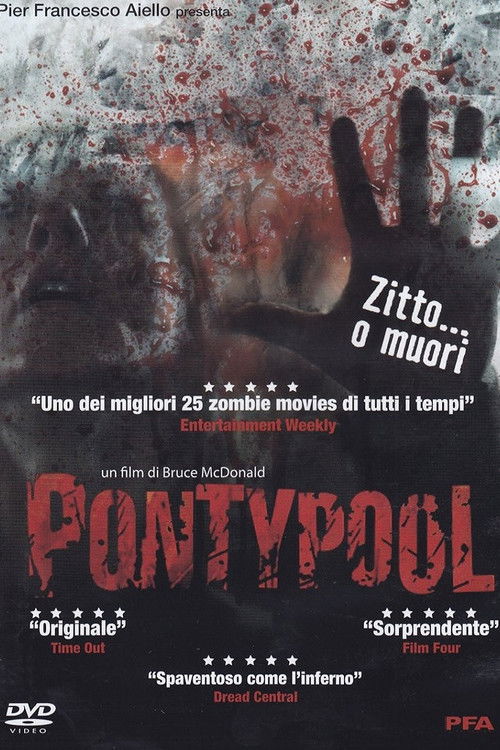

Non è da meno “Pontypool”, filmetto indipendente girato con una manciata di dollari e un pugno di attori che mantiene le stesse regole dei film sopracitati, ma ne sposta l’azione in una stazione radiofonica.

Ma non è questo l’argomento di attenzione del film. L’ambizione del regista e dello sceneggiatore è talmente alta che non solo limitano l’azione ad un luogo tanto piccolo quanto scarico di spunti per un film horror, bensì cercano di realizzare uno zombie movie praticamente senza zombie, utilizzando un singolare (e mai visto prima) metodo di contagio: la parola.

Ebbene si, basta morsi contagiosi, basta virus della rabbia, basta epidemie senza spiegazione. Il contagio è nelle nostre bocche e nelle parole che usiamo. Se si tralascia l’eccezione dell’unica vera scena horror del film, in cui una ragazza infetta sbatte la testa insanguinata contro il vetro della cabina della stazione radiofonica sotto gli occhi spaventati dei superstiti, il resto è fatto soltanto di parole ed è qui che l’idea geniale smette di funzionare. Sulla carta sicuramente ha un effetto, nella trasposizione ha inevitabilmente perso il suo fascino.

Sebbene molti abbiano gridato al miracolo, “Pontypool” avrebbe funzionato alla perfezione come libro o anche solo come sceneggiatura perché nella trasposizione in immagini, dopo un’iniziale curiosità, l’interesse scema scena dopo scena.

L’ultima parte è la causa dell’affondamento dell’intera baracca perché, come espone il detto show don’t tell, mostrare è meglio di raccontare, la spiegazione della motivazione del contagio raccontata nei minimi dettagli risulta priva di mordente e addirittura ridicola.

Si comprendono le motivazioni di una scelta del genere in quanto si tratta di una piéce teatrale per spettatori con gli occhi bendati, di una pellicola raccontata come se il mezzo di trasmissione fosse appunto la radio e non il cinema. Se avessero optato per un finale con qualche immagine in più e qualche parola meno, e perché no, con l’aggiunta di qualche zombie, forse adesso staremmo parlando di cult.

Un’occasione sprecata perché con un’idea così buona in mano, un’argomentazione forte e anche carica di simbolismi (il potere della comunicazione) si poteva fare molto di più.

Aggiungere mezza zucca per la bella idea.

Commenti